This post is not meant to shame anyone. But as an honest expression of emotion, I confess I was somewhat disheartened this morning to realize that, out of my core group of co-workers — all of whom I respect as decent, sensible, intelligent people — I’m the only one who will be spending Thanksgiving with ONLY members of my own household.

To be sure, others are scaling back their plans from what they would do in a normal year. Nobody is planning a giant, extended-family feast. Several are taking precautions: gathering outside, or opening windows, eating at separate tables, etc. And I’m grateful for that. Every precaution helps.

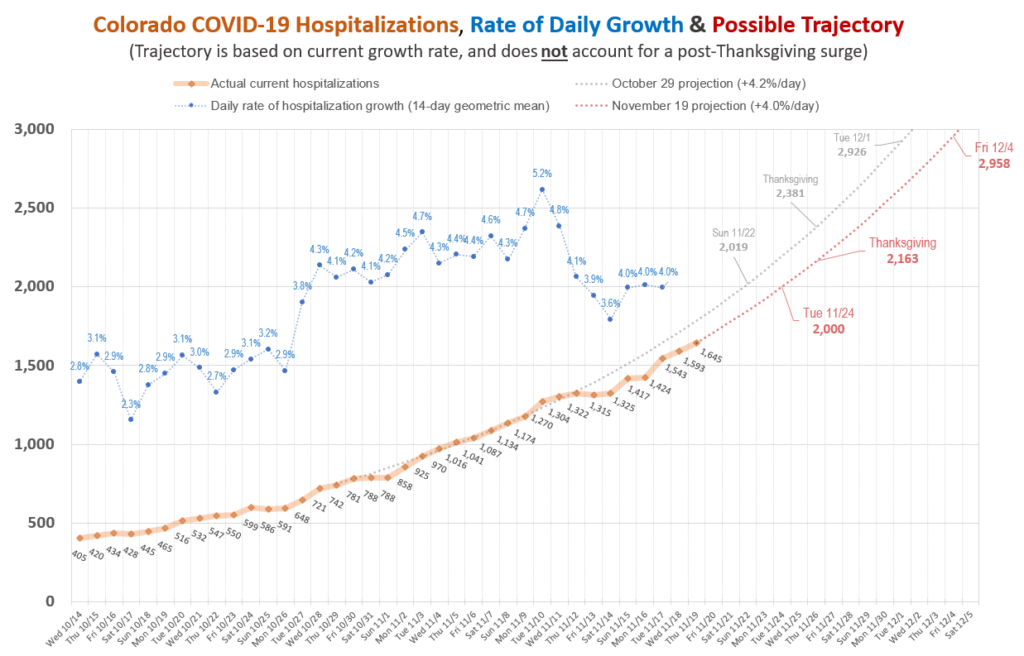

But the fact is, the number of COVID patients in Colorado hospitals, which only reached 1,000 just two weeks ago, is already poised to hit 3,000 the weekend after Thanksgiving — and that’s without a post-Thanksgiving surge.

Becky’s E.R. shifts on Thursday, Friday & Saturday of the holiday weekend will be chaotic enough; the hospital is already well into its crisis contingency plans (and indeed, she’ll be working a different shift than usual, at the hospital’s request, to fill a staffing gap as things get worse). But it’s the next set of shifts, and the ones after that, that I really worry about.

If many thousands of additional Coloradans get sick, all at the same time, in the aftermath of Thanksgiving gatherings, the hospitals — and their heroic nurses and docs — simply won’t have the beds, the resources, or the people to handle it. They just won’t. And so there will be a significant degradation in the level of care, and an escalating level of hell for the staff who have to manage the chaos, and make the impossible, wrenching decisions about who lives and who dies, otherwise antiseptically known as “crisis standards of care.”

And unfortunately, it’s a numbers game. If you have a multi-household Thanksgiving with modest levels of precaution, you’ll probably be fine. The odds are in your favor, and your family’s. But — and here I feel like the guy in “Titanic” talking about the mathematical certainty of doom — the inevitable reality is that some percentage of people who do the same thing you did, won’t be fine. The percentage will be small, but if the denominator is big enough, that small not-fine percentage will amount to enough people that my wife’s workplace will become even more of a hellscape in December than is already guaranteed by the present high level of community spread.

So, yeah, it probably won’t be you, or a member of your family, whose hospital “room” is actually a hallway or closet, or whose bed is at an understaffed convention center. But it’ll be a member of somebody’s family. And likewise, the nurses caring for all those patients, holding down the fort as more patients arrive and more co-workers get sick, will be members of somebody’s family too. And some of them will ultimately be assigned to help palliate the final days & hours of patients stuck in a place like that “pit” in El Paso you may have read about in a viral tweet, which some misinterpreted as whistleblowing about a shocking hospital failure, rather than simply an accurate description of what “crisis standards of care” really means: people, who could otherwise have survived, left to die because of an acute lack of resources, because too many folks took too many risks (in some cases, reckless risks, but other cases, modest, reasonable-seeming risks), at a time when the overall risk to the community is astronomical, and we need to take this even more seriously than we ever have before, including back in March/April.

As I said, I’m not here to shame anyone. I’m not perfect, I haven’t always made the right choices, and I respect all the conflicting emotions at play here. I’ll just say this. Close your eyes and imagine a world where every hospital in Colorado is overrun; there are no beds in the E.R. for heart attack or car accident victims; dozens of refrigerated trucks are serving as mobile morgues all over the state; and the daily nationwide death toll is greater than the number who died on 9/11 (and still rising). And then ask yourself: if I lived in that world, what would I do for Thanksgiving? And then do that. Because that world is our immediate future, unless we very, very seriously buckle down & lock down, right now, today.