As if recent events haven’t created enough cause for #PANIC already, I’ve recently seen a couple of charts of economic data that really put things into (scary) perspective.

One is the “real” monthly employment picture since 2009, subtracting out the 150,000 jobs that must be added per month just to keep up with population growth:

Yikes.

The other requires a bit more explanation. Nate Silver explains:

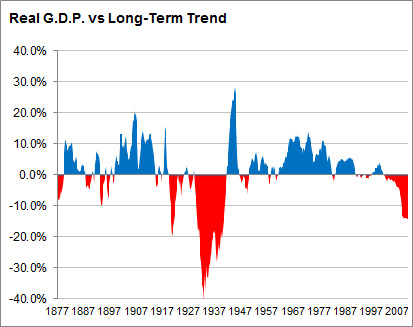

The rate of growth [in the U.S. economy] has in fact been quite steady over the long run: since 1877, the annual rate of G.D.P. growth has averaged about 3.5 percent after inflation. … I’ve plotted how far ahead or below of the long-term trend that the economy is at any given time. …

Here, you can really see the effects of the Great Depression. In early 1933, G.D.P. was about 40 percent below what it “should” have been based on long-term growth rates. But the economy recovered at a rapid clip over the course of the next decade. In fact, G.D.P. temporarily overshot, exceeding the long-term trend during World War II as America employed all the industry and labor that it could get its hands on to help with the war effort.

By this measure, most post-World War II recessions are barely detectable. They look more like reversions to the mean after years of above-average growth.

The Great Recession, however, is highly visible. G.D.P. had already been a couple of percentage points below the long-term trend before it began, as the recovery from the 2001-2 recession was not particularly robust. But things got much worse in a hurry.

Looked at this way, in fact, not only is the worst not yet over — the situation is still deteriorating. Every quarter that the economy grows at a rate below 3.5 percent, it loses ground relative to the long-term trend. Although the economy grew at a 3.8 annual percent rate from fall 2009 through summer 2010, over the past year growth has averaged just 1.6 percent, putting us farther behind.

Right now, gross domestic product is about $13.3 trillion dollars, adjusted for inflation — when it “should” be $15.7 trillion based on the long-term trend. That puts us more than 15 percent below what we might think of as full output, by far the worst number since the Great Depression.

If the economy were to enter another recession and shrink by 1 percent over the course of the next year, we would wind up 19 percent behind the long-term trend. But even if it were to grow at 2 percent, we would still be 17 percent behind.

What we need, instead, is above-average growth — in fact, quite a lot of it. Even if the economy were to begin growing at a 5 percent annual rate, it would take until 2018 for it to catch up to the long-term trend.

Anyone think that’s gonna happen?

Realistically, we’re looking at that ugly red dip extending well into the 2020s. At some point, doesn’t such an extended period of economic difficulty start to approach a functional definition of “depression”? Or at least a “lost decade” or two?

Uh….not a chance.

Yeah…exactly.

In any realistic scenario, we’ll be in the “red” on that chart until the 2020s.

At some point, we come close to a functional definition of “depression,” it seems to me.

Brendan – if you look back in the comments, you will find that I have been saying that this was what was looking like was going to happen (and to continue to happen) as long as our First Occupant continues to fail to learn from history … he might as well be channeling the bad parts of Hoover and FDR when it comes to economics …

You may not respect the folk in government in North Dakota and Texas – but what are they doing right, such that their States’ economies are bucking the national trend ?

You seem to respect the folk in government in California and other blue states – but what are they doing wrong, that other better-performing states are doing right, to keep California and other blue states performing badly ?

At the moment, we are at the beginning of the Obama(/Reid/Pelosi) Depression … that could change in 2012 …

As some of us have been saying for a while, there is a consequence to major federal deficits … Obama and the Dems are managing to make Bush and the GOP mere bush league pikers when it comes to federal deficits … (pun coincidental, yet not unworthy) …

Anyone think that’s gonna happen?

Not as long as the current regime is in power. I include in the regime the Democrats, establishment Republicans, entrenched bureaucracies and revolving door lobbyists.

President Obama needs to rein in his bureaucracies. (such as the E.P.A.) He needs to cut or at least freeze government spending. (not just incrementally reduce the rate of growth)

Republicans and Democrats need to get together in good will and fix our long term liabilities in S.S. and Medicare. If that works, maybe they can fix our tax system, preferably by changing it to a flat tax.

America will recover. We are still the greatest country on Earth, with the strongest economy. We just need to prove that our government can behave to the minimum expectation we have for every family…to live within its means.

Here’s an interesting take on the current situation … after a quick read, I find I can agree with most of it quite easily …

“This is why we should always care about policies that promote growth, because they promote human life. “

Re: the article on RedState that Alasdair linked to:

I certainly agree with the conclusion that economic growth improves the human condition, bur the author does a poor job of backing it up. He conflates technological development with economic growth (though they’re obviously not unrelated), and some of the improvements he touts (lower LA pollution, medical research) were made possible through government regulation or expenditures.

Nothing about this picture changes until we solve one or both of the following:

1. Manipulation of US currency by foreign powers

2. Debt overhang

The first hamstrings domestic labor competing with foreign labor. The second will suppress consumer spending for a generation. The quickest and best solution (in terms of social welfare) is inflation. I don’t see that happening. I think we’ll stay on this crap trajectory until we get a big positive tech shock (lots more production of coal and nat gas, fusion, etc).

Mike R #6 – the author’s point is that, with economic growth and (usually) consequent increased availability of funds for purposes other than basic survival, our species is in a much better position to improve our condition and our lot in Life …

Casey #7 – we can improve our “trajectory” significantly without any need of “big positive tech shock” – all we need to do is get government out of the way of responsible increase in domestic production of energy, both the resources and the final useful version … the technology has been known for decades – 80% of France’s electricity is produced by it, and France still manages to sell electricity to other European countries …

With domestic energy independence we can expect a greatly-decreased ability of “foreign powers” to cause problems for the US …

Yes, I understood the author’s point, and I agree with it.

However, to support his argument, he assumed a directly proportional relationship between the rates of GDP growth and technological development (specifically that reducing GDP growth from 3% to 2% over the past 60 years would turn the world of today into the world of 1991). While there is certainly a mutually-reinforcing relationship between economic prosperity and advancing technology, the formula he uses leads quickly to some obviously incorrect conclusions.

Mike R – a couple of things spring to mind …

Given that correlation is not causation, is there not still good reason to believe that, with lesser growth over the past 60 years, a whole bunch of tech advances and human quality of Life advances would have been made significantly more slowly ? So the 1991 date might have been 1995 or 1987 ?

Secondly – “While there is certainly a mutually-reinforcing relationship between economic prosperity and advancing technology, the formula he uses leads quickly to some obviously incorrect conclusions.” – which obviously incorrect conclusions ?

I notice that another significant group has been drawing some even *more* obviously incorrect conclusions, resulting in the DOW under 11K at the moment … and they are blaming Bush and the Tea Party (and pretty much anyone else than themselves) for it … it’s sorta like the 111th Congress is getting the Little Medieval Warming Period treatment in the now-discredited/now-exposed Hockey Stick curve …

Is it just me ? Or is it genuinely ironic that the eleventy-first Congress were Elites-in-their-own-mind ? (as in a very eleventy-first leet hacker viewpoint/perspective) (not the Lord Of the Rings variant)

1) For the third time, I agree with the conclusion: more money leads to a variety of things that make life better, including better technology.

2) Maybe it’s not that obvious. Anyway, if you extrapolate out to some other scenarios: if GDP were to level off and stop growing altogether (at the current level of around $47k/person), technological development would cease altogether. Even more strangely, during periods of negative growth, progress would actually reverse. As an example, if you use inwarresolution’s math, during the 2008 recession, Apple would have regressed and stopped making iPhones. It’s just silly. As another counterexample, during the Great Depression, significant advances were made in the development of cars and aircraft, even as the economy struggled to get back up to the pre-Depression level.

If the author had used the more general statements that you (Alasdair) have made on the subject, I wouldn’t have a issue. But he spent a big part of the article harping on the 20 years number. Such severe over-precision, when the result forms the emotional core of the article (eg. “a whole generation’s worth of progress!”) is a real problem.

There were other, more nit-picky, things, such as the claim about fuel efficiency in cars, or his distaste for 20-year-old TVs (like the one in my living room, which still has a large, sharp, clear picture, even if it isn’t flat or 16:9). Or how he didn’t address the effect of public policy on one of the core factors in the HDI: education, which can drive long-term growth in both productivity and technology. Or the way that, in the 21st century, technological development is much more uniform around the globe, even when different countries have vastly different economic policies, per capita incomes, and rates of growth.

3) Without getting dragged into the details of the rest of post #11, yes, lots of (or even all) people say incorrect things. Sometimes they’re big and important. So what? The juxtaposition of two wrong things doesn’t make either of them any less wrong.

Regarding that second chart, which shows GDP growth versus the long-term trend, I prefer this depiction better.

As for the general prognosis, I believe this article captures the situation most clearly:

Glenn Reynolds is fond of saying, “What can’t go on forever, won’t.” The modern democratic European nation-state cannot succeed economically into the 21st century if the political dynamic continues to be a redistributive, democratic-socialist left and a nativist, protectionist right. The result is a poison to wealth creation: hampered free trade, needless regulations on energy and food, an overly generous welfare state, oppressive tax rates, and major barriers to the average person’s ability to move up the economic ladder. This unhappy model that is collapsing before our very eyes also happens to be what President Obama has set forth as his goal for America, and even in these early stages of “hope and change”, it’sbeen well past disastrous.

IMO, the proper political dynamism to foster balance between economic growth and “social justice” (I grit my teeth at the concept, but alas, the term is too ubiquitous in the political arena to avoid) requires that the left replace its emphasis on redistributive policies with distributive policies. IOW, the tension should be on wealth and capital creation on the one hand, and distributing the means of capital and production on the other hand. Distributive concepts have been popularized in such notions as “the shareholder society” and underlie many of the education and entitlement reforms now coming out of the Republican Party, but what’s necessary is a realignment that places those reformist proponents at odds with more laissez faire and libertarian-leaning conservatives advocating for privatization and elimination of these sorts of programs — with liberal progressives relegated to the sidelines as a result of the economic dead-end nature of their economic policies.

AML, I’m not ruling out the possibility that the hypothesis you’ve posted is correct. However, I have three big-picture questions about it:

1) Federal revenues as a share of GDP in this country are presently at their lowest rate since the 1950s. Granted, this is partly because of the recession depressing GDP (just as our short-term high deficits are largely because of the recession, not that this stops the entire Republican Party from pretending otherwise, but I digress). However, even during recent boom times, tax revenues were either average or slightly below average. So I’m a bit confused by this notion that we’re suffering under “oppressive tax rates.” That strikes me as being just factually incorrect. Can you enlighten me as to how I’m wrong?

2) Related to #1, if revenues are in fact historically low, or at worst average, and have been higher or equal to their present levels throughout the postwar period, and yet innovation and economic growth proceeded at a delightful pace throughout much of that period….well, doesn’t that completely undermine the hypothesis that our present tax rates, or even moderately increased facsimiles thereof (such as the rates we had, er, throughout much of the postwar period) will prohibitively choke off growth and innovation? Again, what am I missing here?

3) If the answer to #2 is that the tax burden now is falling more disproportionately than before on the “wealth creators”…well, isn’t that, too, just empirically false? Certainly marginal rates on the wealthiest Americans are lower than they often have been, as are corporate tax rates. And the concentration of wealth among the wealthiest Americans has vastly increased in recent decades, while real wages for the middle class have stagnated, which in turn fueled the credit binge as the middle class used debt to create the illusion of the wealth they would have enjoyed if wages hadn’t stagnated. All in all, it doesn’t really seem like the major problem with the American economy right now is that the “wealth creators” and “job creators” (i.e., wealthy people and their companies) are suffering at the expense of the beneficiaries of “redistributive” liberal policies (i.e., poor and middle class people). Again, maybe I’m missing something here. I’m not trying to engage in class warfare. I just want to properly understand the nature of the problem, based on facts rather than ideological bromides from either side.

Would mild marginal tax increases, perhaps with a mildly progressive bent in light of the above-mentioned economic reality, coupled with large-scale but not-totally-crippling spending cuts and entitlement reforms, really cause the destruction of our economy as we know it? How does this theory jive with the historical and mathematical facts?

Brendan, simple answer to 1, 2, and 3: the comment about “oppressive tax rates” was concerning “The modern democratic European nation-state”, not America. Now, I’m certainly up to arguing why present American tax rates are too high (or even oppressive), but the first order of business is to ensure you’re rebutting something I actually said.

More specific answers to your questions and comments:

Granted, this is partly because of the recession depressing GDP (just as our short-term high deficits are largely because of the recession, not that this stops the entire Republican Party from pretending otherwise, but I digress).

Spending increases on a real dollar basis have increased substantially under the Democratic Congress and then under Obama. That is the crux of the problem; the gap between spending and revenue is unnecessarily severe regardless of the recession’s impact on GDP.

However, even during recent boom times, tax revenues were either average or slightly below average. So I’m a bit confused by this notion that we’re suffering under “oppressive tax rates.” That strikes me as being just factually incorrect. Can you enlighten me as to how I’m wrong?

Tax rates are both too high and increasingly inefficient, and this explains why revenues have lagged post-war (WWII) averages. Both parties ought to easily accept the concept that, going forward, tax reform is imperative. The Republican argument for lowering rates in exchange for streamlining the tax code and eliminating writeoffs, loopholes, and so forth ought to be amenable to Democrats when based on static scoring because the evidence from the 1986 Tax Reform strongly suggests that an efficient tax code outperforms in revenue generation what the static scoring models predict. Unfortunately, Democrats are open to closing loopholes and such, but not only are they resistant to lowering rates in return for closing these loopholes and deductions (even though that is what has been recommended by Bowles-Simpson), they want to raise the rates on “millionaires and billionaires” who have joint annual income over $250,000. That is simply unacceptable and demonstrative of their utter lack of recognition of how to get this economy back on track.

2) Related to #1, if revenues are in fact historically low, or at worst average, and have been higher or equal to their present levels throughout the postwar period, and yet innovation and economic growth proceeded at a delightful pace throughout much of that period….well, doesn’t that completely undermine the hypothesis that our present tax rates, or even moderately increased facsimiles thereof (such as the rates we had, er, throughout much of the postwar period) will prohibitively choke off growth and innovation? Again, what am I missing here?

How about, “the facts”? First off, long-term real GDP growth since 1950 has been trending downward (More bad news here). Not coincidentally, the size of the government (local, state, and federal) as a percentage of the GDP has been growing over time to roughly 40% of GDP. Total government revenue lags total government spending, but the trend lines are pretty much the same. The conclusion is inescapable: the more of a chunk government takes out of the economy, the slower the economy grows. This can be likened to, the fatter the man on the horse, the slower the horse can run. Yeah, sure, you still need the jockey to help keep the horse attentive and going in the right direction, but you definitely want a smaller jockey if you want the horse to run faster.

3) If the answer to #2 is that the tax burden now is falling more disproportionately than before on the “wealth creators”…well, isn’t that, too, just empirically false?

Nope! I’m not going to link to all the evidence, but gahrie has thrown up statistics dozens of times around here showing that the top 1% and top 5% pay an increasingly bigger share of the tax burden than they ever have before, and that this is roughly consistent with lower marginal rates. Why? The principle appears to be, the lower the tax rate, the more inclined the wealthy are to pull income out of businesses, and the rich’s share of tax revenue generation rises accordingly. The better question for us to ask is, do higher marginal rates incentivize the rich to hold their wealth in equity, and does that in turn generate jobs and wages for workers because those costs are tax deductible to business profit? I don’t think the answer is clearly yes, but I do admit a balance must be struck there.

And the concentration of wealth among the wealthiest Americans has vastly increased in recent decades, while real wages for the middle class have stagnated, which in turn fueled the credit binge as the middle class used debt to create the illusion of the wealth they would have enjoyed if wages hadn’t stagnated.

You are confusing concentration of wealth with revenue generation i.e. taxes. As I mentioned above, the rich pay a larger share of taxes now than they have in the past when we had higher marginal rates. Tax policy has proven to be a profoundly weak method for redistributing wealth, as the disparity between rich and poor has risen almost universally in advanced nations regardless of their domestic politics. Invariably, wealth is becoming more concentrated as a result of wealth creation through equity generation (i.e., Bill Gates invents Microsoft and owns a major portion of its shares, Microsoft becomes hugely successful, ergo Bill Gates has billions of dollars in paper wealth due to his large ownership stake in Microsoft; the same holds true for Steve Jobs and Apple, the Walton family and Wal-mart, and so on and so on). Higher marginal rates do not make a dent in moving any of that pile from Bill Gates and Steve Jobs to the blue collar worker down the street who is using his home equity line of credit to pay his electric bill while he is out of work. Where higher marginal rates are felt are by the small business owners and the professional class (i.e. the upper-middle class), who derive most of their wealth from salary-type income. That’s ultimately the problem with Democratic tax policies in favor of sticking it to the rich: In their eyes, they are aiming for Bill Gates and trust-fund babies, but in reality they are socking it to their doctors and local business owners.

All in all, it doesn’t really seem like the major problem with the American economy right now is that the “wealth creators” and “job creators” (i.e., wealthy people and their companies) are suffering at the expense of the beneficiaries of “redistributive” liberal policies (i.e., poor and middle class people).

As I’ve illustrated above, with the American economy, “job creators” and “wealth creators” are indeed suffering due to government largesse. Liberal policies result in no real impact on unfavorable/regressive wealth concentration trends, make upper-middle-class folks take home paychecks that feel like middle-middle-class paychecks, kill job creation and wage growth, and increase the number of people dependent on government handouts to get by.

The other reality of liberal policies in play here is the “hidden tax” of regulation and government intervention, which drives a massive, hidden cost that results in no revenue generation for the government (e.g. Sarbanes-Oxley, mileage standards, energy source requirements, development restrictions due to threatened or endangered species, and so on). These “hidden” costs are ever increasing as well. The opportunities to help grease the economic skids here are rampant. An example of this in California a few years back was worker’s compensation, which was so riddled with fraud and legal frailties that it was putting companies out of business, driving multiple attempts at reform.

Again, maybe I’m missing something here.

Yep, quite a bit, actually.

I’m not trying to engage in class warfare.

Heh! Dude, the entire framework of your argument presupposes a liberal progressive stance on notions of social justice and equality. Class warfare flows from that as naturally as lava from a volcano. In any case, the term “class warfare” is such a whitewashing of what it truly is: class envy and hatred of the rich. The rich have no reason to envy or make war on the poor or middle class; class warfare is always a one-way street. Redistributionist policies are simply a macro re-branding of covetousness. Achieving fairness should be about expanding the poor’s access to capital / ownership of the means of production — not taking away from what is already owned by or due to others.

Would mild marginal tax increases, perhaps with a mildly progressive bent in light of the above-mentioned economic reality, coupled with large-scale but not-totally-crippling spending cuts and entitlement reforms, really cause the destruction of our economy as we know it?

The economy is already destroyed as we know it. What makes you think tax increases won’t make it worse? The whole Clintonian argument was that raising taxes might have delayed economic recovery in the early 1990s, but it also lowered the deficit, which allowed Wall Street to settle for lower interest rates, which allowed the average American to gain access to easier terms of credit and expand wealth and economic growth. If I accept that that was actually true in the 1990s, how in the world would raising taxes help when interest rates are already rock-bottom and the flight of capital is away from Europe and into gold and Treasurys? Halting long-term government spending is imperative, absolutely, but expectations of future government spending (or less thereof) does not drive present business investment; in contrast, raising taxes has a very real near-term cost to economic growth.

How does this theory jive with the historical and mathematical facts?

See above. Q.E.D.

@ Brendan 14 — It don’t.

@ AML 13 — You’ve opined in past about specific cases where the equivalence between wealth holders and wealth creators does not hold. Do you think it holds generally? How close do you think the correlation is? I’d love a hypothetical number. I’d put it at about 0.7 (70%) — balancing wealth creation (entrepreneurship) against mere wealth capture (financial manipulation, inheritance, crime, actors and sports stars to an extent, etc.).

The answer matters greatly for policy preferences. For example, one could easily argue that the bulk of entrepreneurial value created over the last 30 years was intimately linked to the university setting, where scientific and technical researchers create but rarely pursue opportunities. In that setting, taxing the wealthy to fund university spending (to an extent) would be productivity maximizing. In the sense of your argument, it would create more wealthy people to tax.

The same argument could easily be made for magnet education, early childhood healthcare, et cetera. Of course, if you have an a priori objection to taxation as such, this is moot anyways.

And in line with Brendan’s argument — if we brought healthcare spending and taxation in line with other first world nations, that would almost close the deficit. If we brought military spending in line, we would run a huge surplus (not going to happen obviously, just making a point).

ACK !

Brendan – Hoover tried increasing tax rates during a recession – and we got the Great Depression …

The effective way to increase tax revenues under current circumstances is to leave tax rates alone, and take a look at those parts of the US economy, States and companies, which are prospering (in spite of Obama/Reid/Pelosi/Geitner) … and then do what those areas/States are doing … I realise that North Dakota is barely fly-over country (being so remote from democrat circles and all), but they are managing to do remarkably well ,b>in spite of the current Federal Government … why is that, you might ask ?

The Dow just went back up a bunch because, so far, the Federal folk have said that they are not going to do anything dumb right now … (grin) … so, as long as Obama doesn’t speak, we may see it continuing to climb …

Specifically addressing your points … (and AML can do this much better than I can) …

1) Federal revenues are down because so many folk who used to be employed in the private sector with themselves and their private sector companies paying taxes … (yes, Government Motors seems to be an exception to that “private sector company paying taxes” thing) … with private sector employment horrendously down, and with public sector employment up too much, since public sector employers don’t pay anywhere near the same amount of taxes (after all, they have no profits to tax), federal revenues are only unexpectedly/mysteriously down in the minds of democrats … for the rest of us, it’s yet another Homer moment … “D’uhhhhh” …

2) Again, the Hoover thing was to increase tax rates during a recession … see the resulting “Great Depression” …

3) Again, you confuse rates with amounts of revenue … would you rather the gov’t take in 30% of $100 or 40% of $60 ? The Great Depression is/was the latter … (I know, oversimplified – hopefully, simplified enough for the d-list folk) …

As I understand it (and AML can correct me if I am wrong), the result of the Bush Tax Cuts was more progressive than the situation before the Bush Tax Cuts … the “Rich” ended up supplying more of teh tax revenues after ’em than they did before ’em …

I’ll take back my flip little comment, as #15 is rather excellent.

I’ll note that the linked tables document an explosion of taxation and spending at the state and local level. Federal taxation is remarkably stable as a fraction of GDP in the postwar period. I’m rather shocked that more isn’t made of this fact in the broader discussion about the size of government. The discussion is always federally focused, when the spending explosion has all been at the state and local level.

If we brought military spending in line, we would run a huge surplus (not going to happen obviously, just making a point).

The 300 pound gorilla you guys always miss when making this point is that the rest of the world has an artificially low military budget, because they expect and know that the United States will and does take up the slack.

At a time when Turkey is going Islamic, Europe is in economic turmoil and dealing with increasing amounts of civil unrest, most of the Middle East is either in revolution or going militant Islamic, when we are fighting terrorism in three countries (and could go to 4 or 5 easily with the same justifications), China is busy arming and developing a blue water navy (including an aircraft carrier and stealth fighters)…can we really afford to slash our military?

As I understand it (and AML can correct me if I am wrong), the result of the Bush Tax Cuts was more progressive than the situation before the Bush Tax Cuts … the “Rich” ended up supplying more of teh tax revenues after ‘em than they did before ‘em

Tax rates can’t get much more “progressive”. In 2008, the bottom 50% of “taxpayers” paid 2.7% of all income tax collected. In a totally fair system, they would pay 50%. In a reasonably progressive system, they might be expected to pay 25%? In our current system, they will soon be paying a negative number, because most of them actually receive a “refund” for more money than they had withheld.

I’ll note that the linked tables document an explosion of taxation and spending at the state and local level. Federal taxation is remarkably stable as a fraction of GDP in the postwar period. I’m rather shocked that more isn’t made of this fact in the broader discussion about the size of government. The discussion is always federally focused, when the spending explosion has all been at the state and local level.

Casey, it’s called Medicaid. Or if you prefer a more general description, unfunded federal mandates.

Wow, so much here today. Here are some not-to-be-taken-seriously notes:

#15: Didn’t we fight a war so that we could stop talking about how we all hate European taxes? BTW, a number of my conservative friends have been forwarding/posting links to that exact article.

I think I heard AMLT hinting obliquely that wealth taxes (as opposed to income taxes) might be an idea worth considering. And also suggesting that higher income taxes on the rich might actually create jobs.

#19: China is currently financing both sides of a potential war between us and them. Plus, directly or indirectly, they manufacture a lot of the supplies that make the American military possible. I feel like, if they actually thought they might go to war with us, they would stop doing that.

Again, to repeat, the above notes are not-to-be-taken-seriously.

This one is a serious comment.

#21: That, and also government employee and retiree health care costs. In some CT municipalities (I’m not really familiar with local budgets elsewhere), I think the rising cost of health care is actually driving something like 100% or more of the *nominal* spending growth.

I think I heard AMLT hinting obliquely that wealth taxes (as opposed to income taxes) might be an idea worth considering. And also suggesting that higher income taxes on the rich might actually create jobs.

Whether or not I am supposed to take you seriously, Mike R, I think you misread me. I’m simply at a loss for how one could interpret my statement, “Achieving fairness should be about expanding the poor’s access to capital / ownership of the means of production — not taking away from what is already owned by or due to others,” as an argument in favor of taxing “wealth”, especially since the sentence immediately preceding that disparaged the concept of redistributive policies. The notion I am advancing is that we should find ways to make working-class folk and the poor shareholders in the means of production. One way to do this would be to give every child at birth $1,000 in an IRA-like account that would be untouchable and held throughout their lifetime until retirement, and their portion of the payroll tax would go to their own account vs. into federal coffers to be spent on current retirees. Another idea is to convert royalties on drilling for oil, natural gas, etc. into shares and dividends distributable on an equal basis to each citizen (similar to Alaska’s system but again, tying the payment to an IRA-like account that has limits on access). I confess I am not the expert on the topic, I am just positing this way of approaching the issue as being far more fair than a Robin Hood tax scheme that endeavors to take from the rich to give to the poor.

What this country really needs is a complete tax reset. We so often get into a lame discussion about taxes being too high, or taxes on the rich not being high enough, and inevitably 99% of the focus ends up on marginal income tax rates. Even when we discuss radical reform, proponents of the flat tax or the national sales tax end up focusing on trying to be revenue-neutral and tying their solution to a particular revenue-as-a-percent-of-GDP target, and give short shrift to the many other forms of income and taxation.

What I’d like to see instead is from-scratch approach, wherein we first list all of the social or economic objectives we intend to reflect in the tax code. For example, I’ll list what I consider to be the top priorities:

1) Encourage an economy that encourages savings and production over consumption.

2) Ensure the free flow of capital to maximize entrepreneurship and wealth creation, and foster the general business climate in a way that maximizes employment.

3) Structure the tax code such that average citizen involvement in tax collection and interface with the IRS is virtually zero, while still relatively straightforward and free of complexities for most businesses.

4) Shape business cost structures in a way that encourages compensation above a certain sustaining level of income to be in the form of ownership stake in the business.

5) Incentivize the rich to hold their wealth in equities over other financial instruments that less directly create jobs (i.e. Treasurys, municipal bonds).

I can certainly see others having some competing priorities:

1) Disincentivize the concentration of wealth.

2) Protect the lower classes from being taxed on income that is required to meet basic needs (food, rent, etc.).

3) Establish a sufficient revenue base for safety net programs / entitlements / universal healthcare.

4) Discourage the exploitation of natural resources and harming of the environment.

5) Mitigate the costs of pollution and environmental degradation by aligning responsibility for the mitigation costs to the source.

Believe it or not, however, I do not believe that these competing agendas necessarily cancel each other out and require one side wins and the other loses. For example, I think we could largely eliminate taxes on corporate profits and instead institute a business-to-business VAT-style tax. This would encourage businesses to integrate vertically and hire more manufacturing and domestic labor instead of outsourcing abroad. I’m opposed to carbon taxes (or credits or whatever), but I’m not opposed to taxing businesses for any sort of emissions that are tied to localized air quality issues (e.g. ozone levels), acid rain, and so on. We could structure taxes in such a way the incentivizes domestic drilling, production, and refining while also ensuring the economic costs of the resulting pollution and end consumption are more closely tied together. We could institute a national sales tax and exempt groceries and clothing items costing under a particular threshold (e.g. $100) in exchange for repealing the income tax. Heck, in that scenario, I’ll even bend on a wealth tax for income over $1,000,000 so long as that is applied no matter the source of income (e.g. dividend, capital gains, wages). We should rely more on use taxes that tie to the true costs of whatever it is being used, governed, and secured/protected (e.g. airports, highways, ports).

The bottom line is we need to start from square one — incremental adjustments and bickering over reform that only discusses marginal rates and eliminating deductions will barely make a dent. We need a tax overhaul that is transformative.

We need a tax overhaul that is transformative.

Throw out the entire current tax code. Flat tax. Corporations taxed as individuals. No deductions, no credits. First bracket starts at 5% at $10,000 of income. Top rate at 33%.Means test SS and Medicare.

#24: To clarify slightly:

It depends on, not so much a misreading, but an intentionally selective (and thus not serious) reading.

You talked about how marginal income tax rates hurt professionals and small businesses, while not actually getting much money out of billionaires. It leads a reader to conclude that, supposing some measure of redistributive tax policies are, shall we say, a political necessity, that a net asset tax (I guess “wealth tax” is too ambiguous) might have its advantages over an income tax.

#25: “Flat tax. … First bracket starts at 5% at $10,000 of income. Top rate at 33%.”

I don’t think this is what most people mean when they say “flat tax”.

gahrie, Mike’s got you nailed. What you might be arguing for is a flatter, simplified income tax, but it’s still not a flat tax. I like the ideological purity of a pure flat tax, but more than likely the best we can do is a two-rate structure that institutes a low rate (~15%) which exempts the first ~$50k of income or whatever, and has the second, steeper rate (~30%) kick in at somewhere north of $1M. However I’d like to see that tax apply equally to all types of income, whether it be wages, capital gains, dividend, or whatever other reportable income, in order to eliminate the desire to shape compensation in response to misaligned tax rates.

You talked about how marginal income tax rates hurt professionals and small businesses, while not actually getting much money out of billionaires. It leads a reader to conclude that, supposing some measure of redistributive tax policies are, shall we say, a political necessity, that a net asset tax (I guess “wealth tax” is too ambiguous) might have its advantages over an income tax.

I abhor that concept. Property is already taxed, but I do not like the idea of equity, bonds, and so forth being taxed. If you tax such things, you encourage a flight of wealth and capital out of the country.

gahrie, Mike’s got you nailed.

OK..call it a plain or simple tax code then.

I like the ideological purity of a pure flat tax, but more than likely the best we can do is a two-rate structure that institutes a low rate (~15%) which exempts the first ~$50k of income or whatever, and has the second, steeper rate (~30%) kick in at somewhere north of $1M

I would oppose any exemption that large. Part of the reason our system is so out of whack is that so many people aren’t paying taxes. I agree with President Obama and the Democrats that we need more shared sacrifice.

Part of the reason our system is so out of whack is that so many people aren’t paying taxes.

I am sympathetic to that argument, but if you get rid of tax credits, exemptions, and deductions and simply exempt the first $X amount of income, you still have even the poorest paying some manner of consumption and use taxes, as well as payroll taxes. Ideally I’d like no income tax at all, but the size of the VAT required to replace that is probably too large to stomach.

There’s a quote, and I wish I could find the source or exact wording. It’s something like:

Conservatives won’t support a flat(/VAT/FAIR/national sales) tax because it would represent a massive revenue stream to fund government programs, and liberals won’t support it because it’s less progressive than the current system. When each side understands what the other side already does, that’s when we’ll get a flat tax.